Unveiling a Century of Change: Most of Taiwan’s Present-Day Mangroves Are Introduced or Artificially Expanded, Not Naturally Native

2025-04-14

興新聞張貼者

Unit秘書室

1,344

Professors Hsi-Te Shih and Chiou-Rong Sheue of the Department of Life Sciences and the Global Change Biology Research Center at National Chung Hsing University, together with Professor Emeritus Yuen-Po Yang of National Sun Yat-sen University, have jointly published a significant new study in the Journal of the National Taiwan Museum, titled “Changes in the Distribution of Mangroves in Taiwan.” This research presents a comprehensive historical review of mangrove distribution in Taiwan, beginning with the earliest documented record in 1864. It draws upon more than 130 domestic and international sources, spanning the Ming and Qing dynasties, the Japanese period, and the modern era.

Through systematic archival analysis and comparison, the study confirms that many of Taiwan’s existing mangrove forests are the result of intentional introductions and human-led plantation efforts, rather than the remnants of naturally occurring native populations. These findings are consistent with earlier research by Dr. Wester in Hawai‘i, and they challenge the popular belief that “mangroves once covered Taiwan’s entire coastline and must now be fully restored.” The study offers a new perspective for the conservation and management of coastal wetland ecosystems.

Professors Sheue and Yang are widely recognized as leading taxonomists in mangrove botany in Taiwan. As early as 2005, they collaborated on issuing Taiwan’s first set of mangrove-themed postage stamps and have published descriptions of several new mangrove species. Prof. Sheue’s work demonstrated that Taiwan’s Kandelia obovata is genetically and morphologically distinct from populations found in India and Southeast Asia. She is also the author of Exploring the Sea Forests: An Introduction to the Indo–West Pacific Mangroves, published by the university press. Prof. Shih is a prominent authority on the biodiversity of coastal crabs in Taiwan and the West Pacific, with over 90 new invertebrate species described to date. His current research focuses on the ecological impacts of non-native mangroves on crab populations and their habitats.

The study reports that while natural mangrove populations once existed in Keelung Bay and Kaohsiung Port (formerly Kaohsiung Bay), these were lost due to development and urbanization. For example, Kandelia obovata had already disappeared from Keelung by the late Japanese period. Kaohsiung’s original mangrove assemblage, once composed of five species (excluding K. obovata), has similarly vanished—likely due to harbor expansion. Today, the only known remaining native population of Avicennia marina survives in Dapeng Bay, Pingtung, with individual trees estimated to be over a century old.

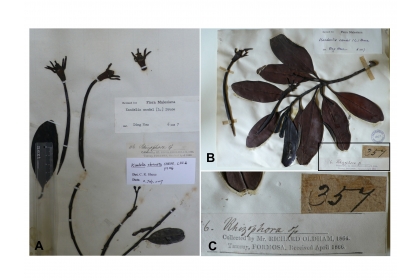

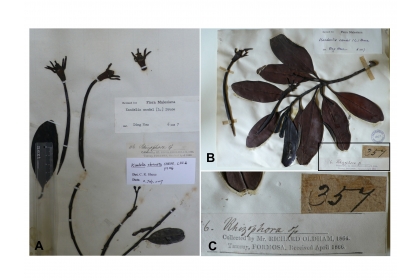

In contrast, mangrove stands in other parts of Taiwan—based on herbarium specimens and historical documents—have been shown to originate from artificial introductions, either during the Qing dynasty (via Fujian and Guangdong) or through post-1945 government-led afforestation programs. For instance, the original K. obovata population at the Tamsui River estuary is thought to have gone extinct in the late 19th century. The current mangroves in that area were introduced around 1925 by a local merchant, Tung-Mao Huang, from Gulangyu, Fujian. Similarly, the K. obovata and A. marina populations in Hongmaogang, Hsinchu, are believed to have been transplanted around 1790 by Hsi-Gung Hsu from Lufeng, Guangdong.

In summary, all extant mangrove forests along Taiwan’s western coast can be traced to human interventions, with no verifiable records of native distribution in those regions.

The research team emphasizes that this study not only provides a revised historical and geographical framework for understanding Taiwan’s mangrove distribution, but also offers crucial insights for shaping future wetland conservation strategies and environmental policies. The authors hope these findings will support the development of a more informed, pragmatic, and sustainable approach to ecological education and governance.

Full article available at:

Through systematic archival analysis and comparison, the study confirms that many of Taiwan’s existing mangrove forests are the result of intentional introductions and human-led plantation efforts, rather than the remnants of naturally occurring native populations. These findings are consistent with earlier research by Dr. Wester in Hawai‘i, and they challenge the popular belief that “mangroves once covered Taiwan’s entire coastline and must now be fully restored.” The study offers a new perspective for the conservation and management of coastal wetland ecosystems.

Professors Sheue and Yang are widely recognized as leading taxonomists in mangrove botany in Taiwan. As early as 2005, they collaborated on issuing Taiwan’s first set of mangrove-themed postage stamps and have published descriptions of several new mangrove species. Prof. Sheue’s work demonstrated that Taiwan’s Kandelia obovata is genetically and morphologically distinct from populations found in India and Southeast Asia. She is also the author of Exploring the Sea Forests: An Introduction to the Indo–West Pacific Mangroves, published by the university press. Prof. Shih is a prominent authority on the biodiversity of coastal crabs in Taiwan and the West Pacific, with over 90 new invertebrate species described to date. His current research focuses on the ecological impacts of non-native mangroves on crab populations and their habitats.

The study reports that while natural mangrove populations once existed in Keelung Bay and Kaohsiung Port (formerly Kaohsiung Bay), these were lost due to development and urbanization. For example, Kandelia obovata had already disappeared from Keelung by the late Japanese period. Kaohsiung’s original mangrove assemblage, once composed of five species (excluding K. obovata), has similarly vanished—likely due to harbor expansion. Today, the only known remaining native population of Avicennia marina survives in Dapeng Bay, Pingtung, with individual trees estimated to be over a century old.

In contrast, mangrove stands in other parts of Taiwan—based on herbarium specimens and historical documents—have been shown to originate from artificial introductions, either during the Qing dynasty (via Fujian and Guangdong) or through post-1945 government-led afforestation programs. For instance, the original K. obovata population at the Tamsui River estuary is thought to have gone extinct in the late 19th century. The current mangroves in that area were introduced around 1925 by a local merchant, Tung-Mao Huang, from Gulangyu, Fujian. Similarly, the K. obovata and A. marina populations in Hongmaogang, Hsinchu, are believed to have been transplanted around 1790 by Hsi-Gung Hsu from Lufeng, Guangdong.

In summary, all extant mangrove forests along Taiwan’s western coast can be traced to human interventions, with no verifiable records of native distribution in those regions.

The research team emphasizes that this study not only provides a revised historical and geographical framework for understanding Taiwan’s mangrove distribution, but also offers crucial insights for shaping future wetland conservation strategies and environmental policies. The authors hope these findings will support the development of a more informed, pragmatic, and sustainable approach to ecological education and governance.

Full article available at: